|

x |

x |

|

|

|

|

INFECTIOUS

DISEASE |

BACTERIOLOGY |

IMMUNOLOGY |

MYCOLOGY |

PARASITOLOGY |

VIROLOGY |

|

|

INFECTIOUS DISEASECHAPTER TEN

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM INFECTIONS

Dr Charles Bryan

Emeritus Professor

University of South Carolina School of Medicine

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Let us know what you think

FEEDBACK |

|

|

|

TEST YOUR KNOWLEDGE

Bacterial

meningitis

Headache and fever

Acute psychosis

Pneumococcal

pneumonia |

|

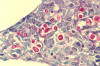

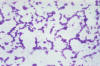

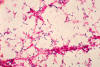

Figure 1

Figure 1

This ventral view of a human brain depicts a purulent basilar meningitis

infection due to Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteria.

Though S. pneumoniae in a normally occurring floral inhabitant of the human

upper respiratory tract, in cases where an individual’s immune system is

compromised, it is responsible for causing paranasal sinusitis, middle ear

infections (otitis media), and lobar pneumonia, as well as meningitis secondary

to these primary respiratory infections. CDC

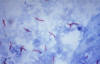

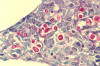

Figure 2

Figure 2

Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteria

grown from a blood culture. Streptococcus pneumoniae, the bacteria

responsible for pneumococcal meningitis, is very common, and normally lives in

the back of the nose and throat, or the upper respiratory tract. CDC

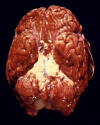

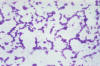

Figure 3 Figure 3

Aerobic Gram-negative Neisseria meningitidis diplococcal bacteria; Mag.

1150X.

Meningococcal disease is an infection caused by a bacterium called N.

meningitidis or the meningococcus. The meningococcus lives in the throat of

5-10% of healthy people. Rarely, it can cause serious illness such as meningitis

or blood infection. CDC

Figure 4

Figure 4

Haemophilus influenzae - coccobacillus prokaryote (dividing); causes meningitis in children, pneumonia,

epiglottitis, laryngitis, conjunctivitis, neonatal infection, otitis media (middle ear infection) and sinusitis in adults

(SEM x 64,000)

©

Dennis Kunkel Microscopy, Inc.

Used with permission

Figure 5

Figure 5

This child has swollen face due to Hib infection.

The tissue under the skin covering the jaw and cheek is infected.

Infection is spreading into her face. She is probably very sick Courtesy of Children's Immunization Project, St. Paul, MN

|

Acute Bacterial Meningitis

Acute bacterial meningitis is a medical emergency variably characterized by

fever, headache, meningismus (stiff neck), nausea, vomiting, and altered mental

status. In about 15% of patients and especially in young children and elderly

patients, the presentation is subtle. Gastrointestinal symptoms may predominate

leading to a misdiagnosis of gastroenteritis. Delayed diagnosis invites tragic

consequences.

The “big 3” causes of community-acquired bacterial meningitis beyond the

neonatal period of life are

Streptococcus pneumoniae,

Hemophilus influenzae type B,

and Neisseria meningitidis. These organisms have in common the ability to

colonize the nasopharynx and to elude host defenses by virtue of their

polysaccharide capsules. Widespread vaccination of young children against H.

influenzae type B now makes this form of meningitis uncommon. N.

meningitidis is a relatively common cause in children, adolescents, and

young adults (See “Meningococcemia” in the chapter on

Sepsis). S. pneumoniae

causes meningitis in all age groups, is the most common cause in older adults,

and is frequent in persons with history of basilar skull fracture.

Listeria

monocytogenes is an important cause in neonates and in patients who are elderly,

debilitated, or immunosuppressed (for example, patients with lymphomas or who

are receiving corticosteroids). Aerobic gram-negative rods are important causes

of meningitis in neonates, elderly patients, and patients who have undergone

neurosurgical procedures.The presentation is, to some extent, age-dependent. Infants may present mainly

with listlessness, poor feeding, and altered breathing patterns. The frail

elderly may present mainly with a decline in the level of awareness. Meningitis

due to Listeria monocytogenes or to aerobic

gram-negative rods usually has a

less dramatic, more sub-acute onset compared to meningitis caused by S. pneumoniae,

H. influenzae type B, or N. meningitidis. When any of the “big

three” cause meningitis in a previously-healthy younger person, the symptoms

usually prompt immediate medical attention. However, the history not

infrequently suggests a nonspecific flu-like illness that gradually worsened

over several days to one week. In this setting, great attention must be paid to

the potential significance of any combination of headache, nausea, and vomiting.

S. pneumoniae is now the most common cause of community-acquired bacterial

meningitis when all age groups are taken into account. Older patients with

pneumococcal meningitis―unlike younger patients with H. influenzae or

meningococcal meningitis―frequently have underlying conditions such as

alcoholism or neurologic disease to which altered consciousness can be easily

attributed. However, patients with pneumococcal meningitis―again, unlike younger

patients with H. influenzae or meningococcal meningitis―frequently have a

clinically-apparent site of infection elsewhere such as

otitis media, sinusitis,

pneumonia, or―rarely―endocarditis.

One should “think meningitis” when patients present with some combination of

fever, headache, stiff neck, nausea or vomiting, and altered consciousness. None

of these symptoms is sufficiently sensitive, however, to exclude meningitis by

its absence. In adults, the overall sensitivity is about 50% for headache and

about 30% for nausea and vomiting. The absence of fever, stiff neck, and altered

mental status allows one to exclude meningitis with 99% to 100% confidence.

Physical examination should target the following areas:

- The skin, looking

for the petechial

rash of

meningococcemia

- The tympanic membranes, looking

for evidence of otitis media as a portal of entry for pneumococcal meningitis

- The optic disks, looking for evidence of

papilledema

as a relative contraindication to lumbar puncture (pulsations in the central

retinal veins effectively exclude increased intracranial pressure)

- Signs of meningeal irritation

Meningeal irritation can be assessed in at least four ways, all of

which can be performed briefly and are therefore recommended:

- Anterior neck flexion. With the patient supine, ask the patient to flex the

head forward (“Put your head on your chest”). Alternatively, ask the patient to

put his or her head between the knees. Neck stiffness is present when the

patient experiences pain on anterior flexion.

- Kernig’s sign: With the patient supine and the hip flexed at 90 degrees, the knee is

extended. Brudzinki’s sign is present when the patient experiences pain or

resistance in the lower back or posterior thigh. This test can also be performed

in the sitting position.

- Brudzinski’s sign: With the patient supine and holding the patient's head,

flex the head so that the chin touches the chest. Brudzinski’s sign is present

when the patient flexes the knees and hips in response to this maneuver.

- The jolt test: Ask the patient to turn his or her head from side to side at a

frequency of 2 to 3 rotations per second. The jolt sign is present when this

maneuver worsens the patient’s headache.

Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s signs have high specificity but low sensitivity for

the diagnosis of meningitis. Jolt accentuation of headache was determined to

have a 97% sensitivity and 60% specificity; in a recent review it was also

concluded that the test has a positive likelihood ratio of 2.2 and a negative

likelihood ratio of zero. It has been suggested that absence of the jolt sign

essentially excludes meningitis. More experience is needed to establish this

point with a reasonable degree of certainty.

When meningitis is suspected, lumbar puncture should be performed. Today’s

frequent tendency to postpone lumbar puncture until a localized intracranial

lesion has been excluded by an imaging study (CT scan or MRI scan) is

unfortunate, because a delay in the institution of therapy of several hours can

be crucial to the outcome. When the illness is acute and there are no localizing

neurologic signs and no evidence of papilledema, the risk-benefit ratio for

lumbar puncture weighs heavily in favor of proceeding with the procedure. Fluid

should be obtained for leukocyte count, differential count, glucose, and protein

content (collectively, these 4 parameters are known as the “CSF formula” and

also for culture. The CSF formula is never diagnostic but can be extremely

helpful, as follows:

- Acute bacterial meningitis: A leukocyte count > 1000/μL with predominance of

polymorphonuclear neutrophils, and with low glucose (< 40 mg/dL or <40% of the

blood glucose) and high protein content (> 150 mg/dL) is highly characteristic.

- Viral (“aseptic”) meningitis: The leukocyte count is usually < 1000/μL with <

50% polymorphonuclear neutrophils on the differential count, with normal glucose

and normal or slightly elevated protein content (exceptions to these rules are

discussed below under “Aseptic Meningitis”).

- Fungal or tuberculous meningitis (chronic meningitis): The leukocyte count is

usually < 500/μL with < 50% polymorphonuclear neutrophils, with low glucose and

elevated protein content.

- Parameningeal infection (such as brain abscess): The leukocyte count is

usually < 1000/μL with < 50% polymorphonuclear neutrophils, normal glucose, and

normal or elevated protein content.

An extra tube of CSF should always be saved, since additional studies may be

indicated if the initial tests are non-diagnostic.

Untreated, meningococcal and pneumococcal meningitis are probably uniformly

fatal. Survivors of H. influenzae meningitis in the pre-antibiotic era often

spent the remainder of their lives in institutions for the severely retarded. |

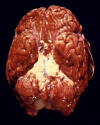

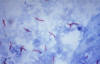

Cryptococcosis of lung in patient with AIDS. Mucicarmine stain.

Histopathology of lung shows widened alveolar septum containing a few

inflammatory cells and numerous yeasts of Cryptococcus neoformans. The inner

layer of the yeast capsule stains red. CDC

|

Aseptic Meningitis, Chronic Meningitis,

and Other Causes of CSF Pleocytosis

There are numerous causes of fever, headache, focal neurologic signs and

symptoms, and CSF

pleocytosis. The more common ones are discussed here because

of the need to distinguish these diverse syndromes and specific diseases from

acute bacterial meningitis.

Aseptic Meningitis (“Viral Meningitis”)

The term “aseptic meningitis” was introduced during the 1930s to describe a

self-limited condition characterized by headache, mild

nuchal rigidity, and

predominantly lymphocytic CSF pleocytosis. The term has been used synonymously

with “viral meningitis,” but it is now recognized that there are many causes of

the aseptic meningitis syndrome including drugs.

Surveillance reports suggest that aseptic meningitis affects about one in 10,000

persons each year; mild cases go unrecognized and the true incidence is unknown.

Rigorous attempts to isolate or identify viruses are successful in the majority

(55% to 70%) of cases. Enteroviruses are by far the most common causes in the

United States (85% to 95% of cases in which a virus is identified). Aseptic

meningitis caused by enteroviruses occurs mainly during the summer and fall.

Infants and young children are most commonly affected. Some of the enteroviruses

can cause a rash. Aseptic meningitis occurs in up to 30% of patients with mumps,

often without evidence of salivary gland disease. The lymphocytic

choriomeningitis virus causes aseptic meningitis with a relatively intense CSF

pleocytosis. This virus is transmitted by rodents such as hamsters, mice, and

rats; hence the disease occurs especially in pet owners, laboratory workers, and

persons living in substandard housing.

Arboviruses such as the St. Louis

encephalitis virus can cause a syndrome resembling aseptic meningitis more than

encephalitis (these terms are relative, since patients with meningitis usually

have some brain involvement and patients with encephalitis usually have some

meningeal involvement). Herpes simplex virus type 2 often causes aseptic

meningitis (in contrast to HSV type 1, which more often causes encephalitis; see

below). Finally, aseptic meningitis is a common manifestation of the acute

retroviral syndrome due to the

human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

Aseptic meningitis can punctuate the course of many systemic bacterial,

rickettsial, mycoplasmal, spirochetal, and parasitic infections. Aseptic

meningitis occurs in syphilis, especially secondary syphilis. Aseptic meningitis

is a prominent feature of

Lyme disease (neuroborelliosis).

Leptospirosis can

cause an aseptic meningitis syndrome during either or both of the two phases of

the disease: the acute infectious phase or the secondary phase during which

manifestations are presumed due to circulating immune complexes. CSF pleocytosis

can occur during the course of bacterial endocarditis as the result of emboli,

immune-complex encephalitis, or possibly mycotic aneurysm. Drugs are being

reported increasingly as a cause of aseptic meningitis. These include not only

drugs used in chemotherapy (such as azathioprine) but also commonly-used drugs

such as NSAIDs, antimicrobial agents (especially TMP/SMX and its separate

components), ranitidine, and carbamazepine (in patients with underlying

connective tissue diseases).

Onset is usually abrupt with headache and mild nuchal rigidity but the more

severe manifestations of acute bacterial meningitis such as stupor and coma do

not occur.

A presumptive diagnosis of aseptic meningitis can be made when a patient with no

history of recent antibiotic therapy presents with headache and mild nuchal

rigidity and is found to have low-grade CSF pleocytosis, predominantly

lymphocytic, with normal CSF glucose and protein levels. The diagnosis is

confirmed by the clinical course, since a self-limited course distinguishes the

illness from chronic meningitis (e.g., tuberculous meningitis and cryptococcal

meningitis). Problems arise when either the clinical course or the CSF formula

is atypical for aseptic meningitis. Some of the agents of aseptic meningitis

(notably mumps and lymphocytic choriomeningitis) not infrequently cause a low

CSF glucose content.

Occasional patients with aseptic meningitis present with headache, mild nuchal

rigidity, and low-grade CSF pleocytosis with a predominance of polymorphonuclear

neutrophils. When the history and physical examination reveal no other signs or

symptoms pointing to acute bacterial meningitis and when the patient does not

look especially “sick,” the clinician faces a dilemma. Should the patient be

hospitalized and committed to a 7- to 10-day course of treatment for presumed

acute bacterial meningitis? Or should the patient be sent home? A third option

is to observe the patient closely without treatment and to repeat the lumbar

puncture in 4 to 6 hours. The second lumbar puncture reveals CSF with a

predominance of lymphocytes, thus pointing to non-bacterial infection. Recently,

the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has been shown to be effective for early,

specific diagnosis of enterovirus infection of the CNS.

All patients with aseptic meningitis should be screened for syphilis with a VDRL

on both serum and CSF. It is prudent to save an extra tube of CSF, since at the

time of initial presentation there is always the possibility that the patient

could have one of the causes of chronic meningitis and further studies may be

necessary. Viral cultures of CSF can be attempted, but are unnecessary in daily

practice.

Chronic Meningitis

The term “chronic meningitis” was introduced during the 1970s to embrace a large

number of illnesses causing meningoencephalitis (fever, headache, lethargy,

confusion, nausea, vomiting, stiff neck) and CSF abnormalities (predominantly

lymphocytic pleocytosis, elevated protein, and often low glucose) lasting at

least 4 weeks. Tuberculosis and

cryptococcosis are the most common causes of

chronic meningitis in the United States.

Etiologies are both infectious and non-infectious. The former include

tuberculosis, fungal diseases (cryptococcosis,

coccidioidomycosis,

histoplasmosis,

blastomycosis,

candidiasis, and

sporotrichosis),

spirochetal

diseases (syphilis and Lyme disease),

brucellosis, and parasitic infections (Acanthamoeba

and Angiostrongylus cantonensis). The latter include tumors,

sarcoidosis,

granulomatous angiitis, Behçet’s disease, and uveomeningoencephalitis. Some

patients are given the diagnosis of “chronic benign lymphocytic meningitis,” and

in other cases a satisfactory diagnosis is never reached. Chronic meningitis is

often a component of diseases manifested mainly as encephalitis (for example,

subacute sclerosing panencephalitis due to the measles virus) or as focal

lesions of the CNS (for example, toxoplasmosis).

The onset is typically insidious but can be acute, mimicking bacterial

meningitis or aseptic meningitis. Patients often present with a one- to

several-week history of headache, fever (which can be low-grade), lethargy, and

nausea. If a diagnosis is not made and treatment instituted, the illness

steadily progresses although the course is sometimes characterized by remissions

and exacerbations.

The key to diagnosis of chronic meningitis is early suspicion and lumbar

puncture. An ample volume of CSF should be saved, since a large number of

studies may be necessary. Initial studies of CSF should include cryptococcal

antigen, VDRL, PCR for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, AFB and fungal cultures (each

preferably on 3 to 5 mL of CSF), and cytospin cytology. All patients should also

have a tuberculin skin test, chest x-ray, and imaging of the brain (CT or MRI

with gadolinium enhancement). Additional studies should be targeted on the basis

of a thorough history and physical examination (both of which may need to be

repeated carefully) and the results of initial laboratory tests. For example,

travel or residence in the southwestern United States suggests

coccidioidomycosis; tick exposures in New England or elsewhere suggest Lyme

disease; and eosinophilia in the CSF suggests Coccidioides, parasites, lymphoma,

or chemicals.

Untreated, tuberculous and cryptococcal meningitis are nearly always fatal. In

previously healthy persons, cryptococcal meningitis can cause a subtle,

extremely indolent illness that culminates in dementia. Prognosis for other

forms of chronic meningitis is variable.

Other Causes of CSF Pleocytosis

There are numerous causes of CSF pleocytosis, of which partially-treated

bacterial meningitis is perhaps the most important to the primary care

clinician. Patients who receive oral antibiotics early during the course of

acute bacterial meningitis may show temporary improvement, and the CSF

pleocytosis may shift from predominantly neutrophilic to predominantly

lymphocytic. The CSF protein usually remains high, helping to distinguish this

entity from more benign conditions. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) may

prove to be highly useful for establishing the diagnosis of partially-treated

bacterial meningitis. Diagnosis of parameningeal infections, discussed further

below, usually hinges on the history, physical examination, and appropriate

imaging studies. Tumors not infrequently cause lymphocytic pleocytosis,

sometimes with low CSF glucose. Seizures sometimes cause mild CSF pleocytosis,

which tends to be predominantly neutrophilic after alcohol-related seizures and

predominantly lymphocytic after seizures caused by stroke. Rare patients

experience recurrent meningitis, the causes of which include leaking cyst

contents from

craniopharyngioma or epidermoid cyst, systemic lupus erythematosus,

and an unusual condition known as Mollaret’s meningitis. Drugs are being

recognized increasingly as a cause of CSF pleocytosis (as discussed in the

previous section on Aseptic Meningitis).

|

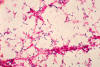

H&E-stained micrograph depicting the histopathologic changes seen in brain

tissue due to herpes encephalitis; Mag. 125x.

Characterized by headaches, fever, and altered mental state due to inflammation

of the brain, herpes simplex virus, the cause of HSV encephalitis, is one of the

main causes for non-epidemic, sporadic encephalitis. CDC

A case of a periorbital fungal infection known as mucormycosis, or phycomycosis.

Mucormycosis is a dangerous fungal infection usually occurring in the

immunocompromised patient, affecting the regions of the eye, nose, and through

its growth and destruction of the periorbital tissues, it will eventually invade

the brain cavity.

CDC/Dr. Thomas F. Sellers/Emory University

|

Encephalitis due to Herpes simplex and Other Viruses

Viral encephalitis is a life-threatening process characterized clinically by

altered consciousness and frequently by focal neurologic signs, seizures, and

other abnormalities. Herpes simplex virus, type 1 (HSV-1) is the most important

cause of sporadic viral encephalitis in the United States, although it accounts

for only about 10% to 20% of the estimated 20,000 cases of encephalitis that

occur each year. Prompt diagnosis is crucial since, in contrast to most of the

other forms of viral encephalitis, specific treatment is available.

The major causes of viral encephalitis are the herpes simplex viruses, the

arboviruses,

mumps,

measles, and

varicella-zoster virus.

Encephalitis due herpes simplex virus

About 95% of cases of encephalitis due to herpes simplex virus are caused by

HSV-1, and the remainder by HSV-2. About 70% of these cases result from

reactivation of latent infection and about 30% result from primary infection.

Why occasional patients infected by this common virus develop encephalitis

remains a mystery. Most severely-affected patients are immunologically normal;

indeed an intact immune system may be required for full expression of the

disease since immunocompromised patients tend to have a milder course. There is

little or no evidence for person-to-person transmission or influence by

environmental factors. By contrast, arboviral infections causing encephalitis

are mosquito borne and tickborne.

Viral encephalitis including HSV encephalitis affects persons of all age groups.

Symptoms and signs of HSV encephalitis usually begins suddenly in contrast to

the usual subacute onset of the other forms of viral encephalitis. The first

symptoms sometimes consist of behavioral abnormalities such as hypomania,

elevated mood, and the Kluver-Bucy syndrome (loss of normal emotional responses

such as anger and fear with hypersexuality). Lethargy progresses rapidly to

confusion, stupor, and coma. Fever is usually present and may be high. Herpes

labialis is present in fewer than 10% of cases and its presence or absence has

no diagnostic significance.

The most characteristic symptoms and signs of encephalitis due to HSV-1 are

attributed to the affinity of the virus for the medial temporal and inferior

frontal lobes. This is manifested by some combination of impairment of speech,

bizarre behavior, and olfactory and gustatory hallucinations. Some patients

develop other localizing neurologic symptoms and signs such as

hemiparesis,

ataxia, or cranial nerve palsies. Focal seizures also occur.

Temporal lobe involvement can be demonstrated by imaging procedures (CT or MRI

scan) or by electroencephalography (EEG). MRI scans are more sensitive than and

specific than CT scans especially during the early phases of the disease. The

EEG shows focal abnormalities in more than 80% of cases. Lumbar puncture usually

discloses red blood cells in the CSF, which reflects the necrotizing nature of

the disease. The white cell count, glucose, and protein content in CSF are

variable and occasionally all of these parameters are within normal limits. The

most important specific test on CSF is the polymerase chain reaction (PCR for

HSV-1 DNA). Reported to be up to 98% sensitive and 100% specific, PCR has

replaced brain biopsy as the diagnostic procedure of choice.

Many diseases can mimic herpes simplex encephalitis. These include vascular

disease, brain abscess or subdural empyema, toxic encephalopathy, tuberculosis,

fungal infections (especially cryptococcosis and mucormycosis), tumor, subdural

hematoma, and connective tissue diseases.

The natural history of encephalitis due to HSV-1 was well characterized prior to

the introduction of effective antiviral therapy. Coma developed in about 85% of

patients, seizures in up to 60% of patients, and aphasia in about 20% of

patients. Mortality was about 70% and there was a high prevalence of neurologic

residua among survivors.

West Nile virus infection

West Nile virus, a mosquito-born infection, is probably the best-documented

example of the introduction of a new, vector-borne human infection into the

United States during the twentieth century. The virus is transmitted by at least

29 North American species of mosquitoes that bite both humans and birds—notably corvids (in North America, crows, jays, and ravens; other corvids in Europe are

rooks and magpies). About 20% of humans infected with the West Nile virus

develop a febrile illness, but only about one-half of these patients seek

medical attention. Approximately one in every 150 infected persons develops

meningitis, encephalitis, or both. Advanced age is by far the greatest risk

factor for severe neurologic disease and long-term morbidity. About one-half of

hospitalized patients have severe muscle weakness. Up to 10% of patients have

flaccid paralysis, sometimes suggesting

Guillain-Barré syndrome. The most

efficient method of diagnosis consists of an IgM antibody ELISA testing of CSF

or serum.

|

|

|

Brain Abscess, Subdural Empyema, and Intracranial Epidural Abscess

The term parameningeal infection (literally, “beside the meninges”) encompasses

several syndromes that require prompt diagnosis and, usually, surgical drainage.

Examples include brain abscess, subdural

empyema, septic thrombosis of the dural

sinuses, and epidural abscess (both intracranial and spinal). Newer imaging

studies (CT scan and MRI) simplify the diagnosis.

Brain Abscess

Brain abscess is usually due to spread from a contiguous focus of infection or

hematogenous spread from a distant site of infection. Examples of the former

include sinusitis (mainly frontal and ethmoid), otitis media or mastoiditis,

dental sepsis, and penetrating injury or neurosurgery; examples of the latter

include congenital heart disease with a right-to-left shunt, hereditary

hemorrhagic

telangiectasia with pulmonary arteriovenous fistulas, suppurative

pulmonary infection, endocarditis, and opportunistic infections arising in

patients who are immunocompromised. Brain abscess can also complicate head

trauma. Streptococci, both aerobic and anaerobic, are the usual isolates but

other aerobic and anaerobic bacteria are often present. Unusual microorganisms

such as fungi and

Toxoplasma gondii cause brain abscess mainly in the severely

immunocompromised.

Brain abscess usually presents with some combination of headache, fever, focal

neurologic deficit, nausea or vomiting, seizures, nuchal rigidity, and

papilledema. However, the presenting symptoms often evolve slowly and are

non-specific. Headache is the most common symptom (70% of patients) and can be

localized or generalized. Fever is present in slightly less than one-half of

adults. Altered mental status and hemiparesis are the most common focal

neurologic signs. Neurologic signs frequently predict the site of disease: for

example, bizarre behavior with frontal lobe abscess; speech abnormalities with

temporal lobe abscess; ataxia, nausea, and

nystagmus with cerebellar abscess;

and visual field cuts with temporal, parietal, or occipital lobe abscess.

Symptoms and signs of the predisposing disease such as sinusitis, otitis media,

dental sepsis, or pulmonary disease are often but not always present.

Subdural Empyema

Subdural empyema, which is less common than brain abscess, arises most often

(60% to 70%) as an extension from sinusitis, especially frontal sinusitis.

Otitis media with or without mastoiditis is the other major cause. Cases also

result from trauma or surgery. Streptococci and especially anaerobic

streptococci are again the most common isolates, but staphylococci (notably, S. aureus) and aerobic gram-negative rods are also encountered. Intracranial

epidural abscess, which is rare, has similar predisposing causes and a similar

microbiology.

Subdural empyema usually evolves more rapidly than does brain abscess.

Typically, symptoms suggestive of sinusitis or of otitis media are followed

within days to several weeks by fever, severe headache, neck pain (meningismus)

and then by altered mental status and focal neurologic signs, sometimes with

seizures. Intracranial epidural abscess, on the other hand, usually develops

slowly over weeks or even months. Nonspecific symptoms give way to symptoms of

increased intracranial pressure (nausea, vomiting, headache, altered mental

status) and focal neurologic signs.

The reported mortality for brain abscess now ranges between 0% and 30% and the

mortality for subdural empyema from 6% to 20%. Many patients, and especially

those with subdural empyema, are often left with a neurologic deficit.

|

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteria,

commonly referred to by the acronym, MRSA; Magnified 9560x

CDC

Spherical (cocci) Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus bacteria

magnified 320X

CDC

Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria

stained using acid-fast Ziehl-Neelsen stain; Magnified 1000X.

CDC |

Septic Cavernous Sinus Thrombosis

Septic thrombosis of the large dural sinuses that provide venous drainage to the

brain is a rare but life-threatening cause of severe headache. Diagnosis is

usually delayed. There are 3 major syndromes: cavernous sinus thrombosis,

lateral sinus thrombosis, and superior sagittal sinus thrombosis. Here we will

focus on the most common of these syndromes, septic cavernous sinus thrombosis.

Facial infections, most often nasal furuncles, precede about one-half of all

cases of cavernous sinus thrombosis. Sphenoid sinusitis accounts for about 30%

of cases, dental infections about 10% of cases, and the remainder of cases are

originate from otitis media, mastoiditis, or other localized infections. Staphylococcus aureus is the most common etiologic agent and the usual cause of

cavernous sinus thrombosis due to facial infections or sphenoid sinusitis. S. pneumoniae and other streptococci explain some cases, and anaerobic bacteria

sometimes cause the condition especially when it is due to dental infection or

other forms of sinusitis. Diabetes mellitus is possibly a risk factor.

Most patients with cavernous sinus thrombosis present with severe, progressive,

unilateral, retroorbital and frontal headache. The illness usually evolves over

several days but in some cases the headache can be subacute or chronic. Migraine

is a common misdiagnosis. Subsequent symptoms include unilateral swelling of the

orbit, diplopia, and drowsiness. Rapid progression of the disease leads to

proptosis,

chemosis,

papilledema, and ophthalmoplegia (inability to move the

eyeball). Close examination often reveals decreased sensation over the forehead,

nose, upper cheek and lip, and cornea and, on ophthalmoscopic examination,

papilledema or dilated and tortuous retinal veins.

Severe unilateral headache with orbital swelling suggests the possibility of

septic cavernous thrombosis, which then needs to be distinguished from other

conditions. Orbital cellulitis is the most common problem in differential

diagnosis. Other possibilities include

blepharitis, intraorbital abscess,

trauma, tumors (meningioma and nasopharyngeal carcinoma), and several rare

vascular diseases. The CSF is usually but not always abnormal. CSF pleocytosis

is present in about two-thirds of cases and in about one-third of cases the CSF

formula suggests bacterial meningitis (see above). Neurodiagnostic

imaging―currently high resolution CT scan with enhancement or MRI scan with

enhancement―is now the diagnostic procedure of choice.

Untreated, septic cavernous sinus thrombosis is nearly uniformly fatal.

Spinal Epidural Abscess

Spinal epidural abscess classically presents initially with fever and back pain

and progresses to weakness of the lower extremities with impaired bowel or

bladder function and then to paralysis. The correct diagnosis is seldom made at

the first patient encounter.

As seen in primary care practice, spinal epidural abscess is usually a

complication of vertebral

osteomyelitis or

diskitis. Bacteria gain access to the

spine through hematogenous dissemination. Most abscesses are located posterior

to the spinal cord, although below the level of the L1 some of them are anterior

to the cord. S. aureus is the most common microorganism, being found in more

than 60% of cases (>90% of cases in some series), but aerobic gram-negative

rods, streptococci, M. tuberculosis, and other organisms are major causes of the

disease. Spinal epidural abscess also occurs as a complication of spinal

surgery, trauma, drug use, or spinal anesthesia.

Many patients first experience a flu-like illness with fever, malaise,

and―especially if S. aureus is the causative organism―myalgias. As the abscess

expands, patients develop severe, localized back pain often accompanied by nerve

root pain. Weakness in the extremities then develops along with sensory changes

and impairment of bladder or bowel function or both.

Untreated, spinal epidural abscess progresses to complete compression of the

spinal cord with permanent paralysis.

|

|

|

Return to the Infectious Disease Section of Microbiology and Immunology On-line

Return to the Infectious Disease Section of Microbiology and Immunology On-line

This page last changed on

Tuesday, February 17, 2015

Page maintained by

Richard Hunt

|