| x | x | |||||

|

||||||

| INFECTIOUS DISEASE | BACTERIOLOGY | IMMUNOLOGY | MYCOLOGY | PARASITOLOGY | VIROLOGY | |

|

|

||||||

|

Let us know what you think FEEDBACK |

||||||

| SEARCH | ||||||

|

|

||||||

|

All

life cycle diagrams in this section are courtesy of the

DPDx

Parasite Image Library

PART ONE |

Ticks are found worldwide. They are blood-sucking, opportunistic parasites that can attach to the skin of a variety of vertebrate hosts. They have no segmentation and are dorso-ventrally flat with four pairs of legs (figure 1). Although all stages of the tick life cycle can suck blood, it is normally the adult tick that poses a problem for humans. Human tick-associated diseases are most common in the summer months when the likelihood of contact increases during outdoor activities, usually in wooded areas. Being bitten by a tick is often painless and the presence of the tick may not be detected for some time. Often the tick poses no problem for the human host other than an erythromatous papule and it drops off after engorging on blood. Sometimes, the site of attachment may itch and become painful. Secondary infections of the wound site may occur, often as a result of the mouthparts remaining attached after the tick is removed. Ticks can attach anywhere on the body but are frequently found at the hairline, around the ears, groin, armpits etc. Whilst the bites of most ticks are inconsequential, they can carry a number of human disease agents including viruses, bacteria and protozoa. There are two families of ticks: the hard ticks (Ixodidae) and the soft ticks (Argasidae) (figure 1). The Ixodidae attach to their host over a prolonged period of time (several days) while the Argasidae feed rapidly and then drop off. Consequently, they are frequently undetected. Although most tick-associated problems arise from disease-causing organisms carried by the ticks, in one case – tick paralysis – the problem arises directly from toxins in the tick’s saliva. Important disease-carrying ticks in the United States are: HARD TICKS Dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis) (figure 2 and 3A,B) which is found east of the Rocky Mountains and in some areas of the Pacific coast states Rocky Mountain Wood Tick (Dermacentor andersoni) (figure 3 C,D). As its name suggests, it is found in the Rocky Mountains and also in southwest Canada Deer Tick (Black-legged tick) (Ixodes scapularis) (figure 3 G,H, K). This occurs in the north east and north central United States. Western black legged tick (Ixodes pacificus) (figure 3 I,J) which is found in the Pacific coast states of the United States. Brown dog tick (Rhipicephalus sanuguineus). Also known as the red dog tick (figure 3 M). This is found world-wide (all over the US and also southeast Canada) and can complete its entire life cycle indoors. It primarily infests dogs but can feed on other mammals including man. Lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum) (figure 3 E,F), found in south eastern and south central United States. SOFT TICKS

|

|||||

|

Figure 3 (below) |

||||||

A. American dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis) CDC |

C. Rocky Mountain wood tick (Dermacentor andersoni) CDC

E. Blacklegged tick (Ixodes scapularis) CDC

H. Approximate distribution of the lone star tick CDC

J. Approximate distribution of the western blacklegged tick CDC

|

|||||

Figure 4 Reported cases of Rocky Mountain spotted fever in the United States, 1942-1996

Figure 5. Seasonal distribution of reported cases of Rocky Mountain spotted fever, 1993-1996 CDC

Figure 6. Rickettsial and Orientia infection of endothelial cells

Figure 7. Gimenez stain of tick hemolymph cells infected with R. rickettsii CDC

Figure 8. Characteristic spotted rash of late-stage Rocky Mountain spotted fever on legs of a patient, ca. 1946 CDC

Figure 9. Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever: Early (macular) rash on sole of foot CDC

Figure 10. Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever: Late (petechial) rash on palm and forearm CDC  Figure 11. This lesion, caused by Rocky Mountain spotted fever, is located on the roof (hard palate) of this child's mouth. CDC |

DISEASES FOR WHICH HARD TICKS ARE CARRIERS BACTERIAL DISEASES Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever There are several hundred reported cases of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever each year in the United States (ranging, during the past half century, from a low of about 200 to more than 1200 in the early 1980’s). The numbers are again rising (figure 4). Most at risk are children under 15 years of age. Usually, cases occur in the summer because of higher numbers of ticks and more frequent contact of humans with ticks (figure 5).

|

|||||

Figure 12.Thumb with skin ulcer of tularemia. CDC/Emory U./Dr. Sellers

Figure 16. Average annual incidence rate of tularemia by sex and age group - United States, 1990-2000 CDC

|

Tularemia This is also carried by the two Dermacentor species. Tularemia is caused by the bacterium Francisella tularensis, which is carried by rodents, rabbits and hares; as a result tularemia is otherwise known as rabbit fever. One of the several ways that humans can be infected is by being bitten by a tick that has acquired the bacterium after biting one of these animals; however, it can also be inhaled during the handling of infected rodents. There have been no reports to person-to-person transmission. Francisella tularensis is very infectious. Tularemia occurs all across the continental United States but is relatively rare, with about 200 cases being reported each year (figure 15, 16).

|

|||||

Figure 17. Coxiella burnetii , the organism responsible for Q fever

|

Q Fever

|

|||||

Various farm animals (cattle sheep goats etc) are the primary carriers of the bacterium Coxiella burnetii (figure 17) which causes Q fever. Spread to humans is usually via inhalation of dust containing dried urine, feces etc of infected animals. However, less commonly, the bacterium can be transmitted via the bite of Dermacentor ticks. Ingestion of contaminated milk can also lead to infection. C. burnetii infects macrophages and survives in the phagolysosome, where the bacteria multiply (figure 18). The bacteria are released by lysis of the cells and phagolysosomes.

Symptoms

Acute Q fever

Many patients, about half, show no signs of infection but in others after an incubation period of 1 - 2 weeks, there is a sudden onset of fever, headache, general malaise, myalgia, sore throat, chills, sweats, non-productive cough, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and chest pain. The patient may also appear confused. Many patients go on to the symptoms of pneumonia and hepatitis but most recover in a month or two without treatment although acute Q fever has a mortality rate of 1-2%.Chronic Q fever

If the patient fails to resolve the infection, chronic Q fever results. This can occur a few months after primary infection but can also occur many years later. Endocarditis of the aortic heart valves is the major problem that arises. This usually occurs in people with heart valve disease but also at risk are transplant, cancer and kidney disease patients. The chronic form of Q fever has a fatality rate of about 60 - 70%.Diagnosis

Serology to determine the presence of antibodies against Coxiella burnetii is used.Treatment

Antibiotics such as doxycyline are used to treat acute Q fever. For chronic Q fever, two protocols have been investigated: doxycycline along with quinolones for at least 4 years and doxycycline with hydroxychloroquine for 1.5 to 3 years.There is a vaccine used in Australia for persons who may come in contact with C. burnettii but it is not commercially available in the United States.

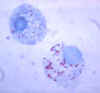

Figure 19. Infection of leukocytes by Ehrlichia

Figure 20. Reported Cases of Ehrlichiosis in the United States CDC

Figure 21. Areas where human ehrlichiosis may occur based on approximate distribution of

vector tick species CDC

Figure 22. Approximate seasonal distribution of HGE in the United States CDC

Ehrlichosis

Human Ehrlichiosis

Human ehrlichiosis is carried by Dermacentor variabilis and by Amblyomma americanum and is caused by a number of bacteria of the Ehrlichia family, in the United States principally by Ehrlichia chaffeensis. These bacteria are small gram-negative organisms that infect leukocytes (figure 19). As with many tick-borne diseases, incidence follows vector distribution (figure 21) with higher incidence during the summer months (figure 22) when tick populations and contact with them are higher. The number of cases has been increasing (figure 20).

Symptoms

After an incubation of period of a week to 10 days, the patient presents with myalgia, headache and general malaise. There can also be nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, cough, joint pains and the patient may be confused. Sometimes, there is a rash but this is normally only in pediatric cases. If left untreated, more severe manifestations of the infection can occur, including prolonged fever, renal failure, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, meningoencephalitis, adult respiratory distress syndrome, seizures, or coma. Mortality rate at this stage is 2 - 3%. More at risk are immune-suppressed patients.Diagnosis

Microscopy using blood smears or serology to detect anti-Ehrlichia antibodies can be used.Treatment

Antibiotics such as doxycycline are the recommended treatment.

Human Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis

Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis is caused by a species of Ehrlichia similar to species found in animals (Ehrlichia equi and Ehrlichia phagocytophila) and is transmitted by blacklegged ticks (Ixodes scapularis) and western blacklegged ticks (Ixodes pacificus).

Figure 23. Lyme disease risk by region of United States CDC

Figure 24.

Lyme disease rash CDC

Figure 25. Morphology of Borrelia burgdorferi. Dark

field image ©

Jeffrey Nelson, Rush University, Chicago, Illinois

and

The MicrobeLibrary

Figure 25. Morphology of Borrelia burgdorferi. Dark

field image ©

Jeffrey Nelson, Rush University, Chicago, Illinois

and

The MicrobeLibrary

Lyme Disease

Lyme disease is caused by the spirochete bacterium, Borrelia burgdorferi (figure 25), which typically infects small mammals in the northeast and north central United States. It is transmitted to humans by Ixodid black legged ticks (deer ticks). There are over 20,000 cases per year in the United States making it the most common tick-borne disease in North America. The disease was first described from the town of Old Lyme in Connecticut but is found on both the east and west coasts and in the Mississippi valley (figure 23). In Europe, a similar disease is caused by Borrelia garinii or Borrelia afzelii.

Symptoms

Fever, headache and malaise and a characteristic rash named erythemia migrans (figure 24), which can occur in a few days but sometimes only after a few weeks, are typical of Lyme Disease. The rash (which is usually not painful) often has a bull’s eye appearance since as it grows (up to 30 cm across) the central region clears. If left untreated, the infection spreads and can result in Bell’s Palsy (partial paralysis of muscles in one or both sides of the face), meningitis, heart palpitations and severe joint pain. These symptoms usually resolve in a few weeks but after several months about 60% of patients will get severe joint swelling and arthritis. A small minority may also get neurologic symptoms (tingling of the extremities, shooting pains, numbness)

Treatment

Early administration with antibiotics (doxycycline, amoxicillin, or cefuroxime axetil) is recommended. Some patients continue with neurological and muscle pain problems even after antibiotic treatment. It is not known what causes these but they may be autoimmune in nature.Diagnosis

Various laboratory tests include Elisa, western blot

Southern Tick-Associated Rash Illness

This rash is similar to that seen in Lyme disease. The causative organism is not known but it is not Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease agent. The lone star tick, Amblyomma americanum, is the transmission vector.

Symptoms

Malaise, fever, myalgia, arthralgia and a “bulls eye” rash at the site of the tick bite. There are no chronic neurological symptoms as are seen with Lyme disease

Treatment

The usual oral antibiotics are used and the symptoms quickly resolve.

Figure 27. Infection with Babesia. Giemsa-stained thin smears. Note the tetrad (left side of the image), a dividing form pathognomonic for Babesia. A 6 year old girl, status post splenectomy for hereditary spherocytosis, infection acquired in the US. CDC

Figure 28. Thin blood film of B.

microti ring forms with a typical Maltese Cross (four rings in cross

formation). © MicrobeLibrary and Lynne Garcia,

LSG & Associates

PROTOZOAL DISEASES

Babesiosis

Babesiosis is carried by species of Ixodes including the deer tick (Ixodes scapularis) in the north and mid-west of the United States and in other countries, including Europe. Babesia microti is the usual causative organism and is a hemoprotozoan (i.e. it circulates in the bloodstream). Normally, the two hosts of Babesia microti are ticks and peromyscus mice (Peromyscus leucopus). The tick infects the mice with sporozoites, which reproduce asexually in erythrocytes. These escape to the blood stream where they may form male and female gametes that are taken up by the tick during a blood meal. In the tick, the gametes fuse and go through a sporogonic cycle to form more sporozoites. Humans can also acquire sporozoites when bitten by an infected tick and are usually dead-end hosts but babesiosis has been transmitted to other humans via blood transfusions (figure 29).

In most cases, infection is asymptomatic but after a week to a month, symptoms can appear. These include fever, chills, sweating, myalgias and fatigue. In severe cases, hepatosplenomegaly and hemolytic anemia can occur. Normally, the patient recovers, although severe cases occur in immuno-compromised patients and the elderly.

Disease caused by another protozoan, Babesia divergens, can result in more severe and sometimes fatal cases of babesiosis.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is by serology, immunofluorescence microscopy and by direct observation of the parasite in blood smears in which “Maltese Cross”-like inclusions in erythrocytes are seen (figure 27, 28). These consist of four budding merozoites attached together.

Treatment

Usual antibiotics used are clindamycin plus quinine or atovaquone plus azithromycin.

Figure 29

Figure 29The Babesia microti life cycle involves two hosts, which includes a rodent, primarily the white-footed mouse, Peromyscus leucopus. During a blood meal, a Babesia-infected tick introduces sporozoites into the mouse host

Figure 30. Isolated female patient diagnosed with Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever

CDC

Figure 31. Isolated male patient diagnosed with

Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever.

Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever is a tick-borne hemorrhagic fever. CDC

VIRAL DISEASES

Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever

This is caused by a Nairovirus, a member of the Bunyaviridae. It is found in Eastern Europe and throughout the Mediterranean areas of southern Europe, the Middle East, Africa, northwestern China, central and south Asia. Ixorid ticks (genus Hyalomma) spread the virus, which is also carried by numerous species of domestic and wild animals. Person to person transmission through infected blood and other body fluids has been documented.

Symptoms

Initially, the patient presents with headache, high fever, back pain, joint pain, stomach pain, and vomiting. There may be flushing, red eyes and throat and small red spots called petechiae on the palate. Hemorrhage ensues after a few days and lasts for a few weeks (figure 30, 31). This is indicated by severe bruising, nosebleeds, and failure to stop bleedings after a cut or injection. Slow recovery often ensues but mortality can be as high as 50%.

Treatment

Since this is a viral disease, treatment is largely supportive with particular attention to electrolyte balance. Ribavirin has been used. An inactivated vaccine has been used in Eastern Europe.

Colorado Tick Fever

This is sometimes confused with a mild case of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever but Colorado Tick Fever is caused by a coltivirus, a member of the reoviruses. They are endemic to north western North America and are found in Ixodid ticks. The virus distribution closely matches that of its vector, Dermacentor andersoni.

Person-to-person transmission can occur by blood. Prolonged viremia observed in humans and rodents is due to the intraerythrocytic location of virions, which protects them from immune clearance.

Symptoms

Infection results in abrupt fever, chills, headache, retro-orbital pain, photophobia, myalgia, abdominal pain, and malaise. Sometimes fever can be diphasic or triphasic, usually lasting for 5 to 10 days. Severe forms of the disease that involve infection of the central nervous system or hemorrhagic fever, pericarditis, myocarditis, and orchitis have been rarely observed, mainly in children. Severity is sufficient to result in hospitalization of approximately 20% of patients. There has been evidence of transmission from mother to child.

Far Eastern Tick-Borne Encephalitis

(Also known as Russian spring-summer encephalitis or Taiga encephalitis)

This is caused by a flavivirus which is spread by

ixodid ticks (Ixodes persulcatus, I. ricinus and I.

cookie). Small animals are the reservoir and the virus is endemic to the

former Soviet Union and parts of eastern and central Europe.

Symptoms

About two weeks after infection, there is a mild influenza-like disease that normally resolves in a few days but which can be followed by meningitis and meningoencephalitis in about one third of cases. In some cases, there may be partial paralysis and mortality may be as high as 25%.

Treatment

Supportive care is normal. There is a vaccine of killed virus that is available in Europe.

Powassan Encephalitis

This is a rare disease caused by a flavivirus carried by Ixodid ticks. There has been less than one case per year reported in the United States but mortality is high. It is widespread in North America and is found in small animal populations including woodchucks.

Symptoms

After a relatively long incubation period of up to one month, the patient may present with a sore throat, dizziness, headache and confusion. This can proceed to general malaise, vomiting, respiratory distress, fever and convulsions, which then lead to paralysis and possibly coma. Because the virus attacks brain tissue, survivors can have severe neurological problems.

Treatment

Supportive care is indicated.

Tick-Borne

Encephalitis

(Also known as biphasic meningoencephalitis, central

European tick-borne encephalitis, Czechoslovak tick-borne encephalitis, diphasic

milk fever or viral meningoencephalitis)

This disease results from infection by tick-borne encephalitis virus, which is a member of the Flaviviridae.

Symptoms

Tick-borne encephalitis starts as mild influenza-like symptoms with fever accompanied by leuko- and thrombocytopenia. This resolves within a few days. However, about one third of patients develop meningitis and meningoencephalitis. This can, in a few cases, be followed by paralysis. The European form of the disease has a mortality rate of under 5%. Most patients recover but about a third may have long-lasting neurological problems.Treatment

Supportive is indicated. There is an experimental killed vaccine in Europe. In Sweden TBE vaccination is recommended for residents of and regular visitors to TBE endemic areas.

Kyasanur Forest Disease

This disease is similar to Russian spring-summer encephalitis and is also caused by flaviviruses. It is found only in the Kyasanur forest of Northern India. The disease occurs during the dry season as its tick vector (Haemaphyalis spinigera) begins to feed on humans. Local carriers are shrews and monkeys.

Louping Ill Virus

This is found in the British Isles and is caused by a flavivirus that is carried by pheasants and sheep, among other animals. It can infect many hosts via the tick vector, Ixodes ricinus. It causes mild encephalitis that gives the infected animal an unusual gait (hence its name). However, it can kill livestock and humans not given proper supportive care.

DISEASE CAUSED DIRECTLY BY HARD TICKS

Tick Paralysis

In addition to being carriers of disease-causing microorganisms, some ticks (Amblyomma americanum and the two Dermacentor species) can cause tick paralysis. This is a rare disease caused by toxin in the saliva of the tick and results in an acute, ascending, flaccid paralysis caused by reduced acetyl choline or motor neuron action potentials. The paralysis, which is not associated with pain, starts a few days after the bite and comes on gradually over a period of days. The paralysis resolves surprisingly rapidly, usually within a day of the removal of the tick but if the tick is not removed the mortality rate, as a result of respiratory paralysis, can be as high as 10%. Tick paralysis can be confused with other acute neurologic disorders or diseases (e.g., Guillain-Barré syndrome or botulism).

WEB RESOURCES

EMERGING AND INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Coltiviruses and Seadornaviruses in North America, Europe, and Asia|

CDC

CASE REPORT

Cluster of Tick Paralysis Cases ---

Colorado, 2006

DISEASE FOR WHICH SOFT TICKS ARE CARRIERS

BACTERIA

Tick-Borne Relapsing Fever

Tick-borne relapsing fever is a rare disease (about 25 cases per year in the United States) and is caused by several spirochete bacterial species of the Borelia family. The transmission agents are soft ticks of the genus Ornithodoros. Soft ticks (family Argasidae) differ in many ways from the so-called hard ticks (family Ixodidae), but the most important is that they take brief meals from their host and then drop off. The bite is usually painless. Thus, they are far less likely to be found than the hard ticks that stay attached while feeding for hours. In the wild, these ticks are found in nesting materials when not feeding on their animal host. All stages of the life cycle can take blood meals.

The individual Borrelia species that cause tick-borne relapsing fever are usually associated with specific Ornithodoros tick vectors. B. hermsii is transmitted to humans by Ornithodoros hermsi, B. parkerii is transmitted by Ornithodoros parkeri and B. turicatae is transmitted by Ornithodoros turicata. Each tick is associated with a preferred environment and hosts. Ornithodoros hermsi is found at higher altitudes (1500 – 8000 feet) where it is associated usually with ground squirrels, tree squirrels and chipmunks. Ornithodoros parkeri occurs at lower elevations and inhabit caves and the burrows of ground squirrels, prairie dogs and burrowing owls. Ornithodoros turicata occurs in caves and ground squirrel, prairie dog or burrowing owls burrows in the plains regions of the Southwest United States.

Symptoms

Initially, the patient experiences arthralgia, myalgia, headache, chills and fever. This is followed by nausea, cough, photophobia, and dizziness. The patient may be confused. There is often a rash. The incubation period before the onset of the first symptoms is about a week (though it can be shorter or longer). After the onset of disease, symptoms last a few days and then resolve. After a week or two, the symptoms reoccur and in the absence of treatment, recurrence continues for several more episodes. As the fever resolves, the patient may go through a crisis in which first there is a high fever accompanied by confusion and delirium. This “chill phase” lasts up to half an hour. Then there is the “flush phase” in which the temperature drops accompanied by profuse sweating and sometimes a drop in blood pressure.Diagnosis

Microscope smears of blood, bone marrow or cerebrospinal fluid stained with Giemsa or acridine orange. Serologic testing is also available.Treatment

Antibiotics are used and symptoms resolve a few days. There can, however, be long-term sequelae including heart and kidney problems, peripheral nerve involvement, ophthalmia, and abortion. Without treatment mortality may be up to 10% of patients.

![]() Return to the Parasitology Section of Microbiology and Immunology On-line

Return to the Parasitology Section of Microbiology and Immunology On-line

This page last changed on

Saturday, February 14, 2015

Page maintained by

Richard Hunt