|

x |

x |

|

|

|

|

INFECTIOUS

DISEASE |

BACTERIOLOGY |

IMMUNOLOGY |

MYCOLOGY |

PARASITOLOGY |

VIROLOGY |

| |

CHAPTER NINETEEN - HEPATITIS

PART ONE - DISEASE TRANSMITTED ENTERICALLY

HEPATITIS A AND E

Dr Richard Hunt

Professor

Department of Pathology, Microbiology and Immunology

University of South Carolina School of Medicine

|

|

EN

ESPANOL -

SPANISH |

| |

| |

| |

|

Let us know what you think

FEEDBACK |

|

SEARCH |

|

|

|

|

Logo image © Jeffrey

Nelson, Rush University, Chicago, Illinois and

The MicrobeLibrary |

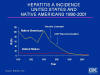

Figure 1

Figure 1

Acute Viral Hepatitis by Type, United States, 1982-1993

CDC |

The five viruses described in Chapter Eighteen cause

hepatitis. "Infectious hepatitis" is caused by hepatitis A virus (HAV); "serum

hepatitis" results from hepatitis B virus (HBV) and the delta agent (HDV).

"Non-A, non-B hepatitis" is caused by hepatitis E (HEV) and hepatitis C (HCV)

viruses (figure 1). HAV and HEV are transmitted

enterically, while HCV, HBV

and HDV are transmitted

parenterally. There are more than 700,000 cases of

viral hepatitis per annum in the United States, of which more than half are

asymptomatic. Despite the availability of highly effective vaccines against

hepatitis A and hepatitis B, these diseases are among the most reported

vaccine-preventable diseases in the United States.

|

Virus |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

G |

| Disease |

Infectious hepatitis |

Serum hepatitis |

Non-A, non-B hepatitis

Post transfusion hepatitis |

Delta agent |

Enteric non-A, non-B

hepatitis |

|

| Source |

Feces |

Blood and body fluids Sexual contact |

Blood and body fluids Sexual contact |

Blood and body fluids Sexual contact |

Feces |

Blood and body fluids |

| Transmission |

Enteric Fecal-Oral |

Parenteral Percutaneous

Permucosal |

Parenteral Percutaneous

Permucosal |

Parenteral Percutaneous

Permucosal |

Enteric Fecal-Oral |

Parenteral Percutaneous

Permucosal |

| Sexual transmission |

Yes (especially homosexual) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Chronic infection |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

| Incubation period |

15 - 20 days |

45 - 160 |

14 - 180 |

15 - 64 |

16 - 60 |

? |

| Carcinogenesis |

No |

Hepatocellular carcinoma |

Hepatocellular carcinoma |

Hepatocellular carcinoma |

No |

? |

| Cirrhosis |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

? |

| Severity of disease |

Usually mild. Very low mortality |

Sometimes severe 1 -2% mortality |

Usually (80%) asymptomatic Up to 4%

mortality |

Super-infection with HBV - often very

severe with high mortality rate Co-infection with HBV - often severe |

Usually mild except in pregnancy |

Asymptomatic to mild |

| Prevention |

Vaccine |

Vaccine |

Behavior Modification Blood

screening |

Behavior Modification HBV vaccine |

Safe water No vaccine |

|

| Chemotherapy |

|

|

Peginterferon/ Ribovirin |

|

|

|

| United States chronic infections

(total) |

None |

1- 1.25 million |

3.5 million |

70,000 |

None |

|

| United States acute infections per

year (estimated) |

125,000 to 200,000 |

140,000 to 320,000 |

35,000 to 180,000 |

6,000 to 13,000 |

|

|

| United States Deaths per year from

fulminant hepatitis |

100 |

150 |

? |

35 |

None |

? |

| United States Deaths from chronic

liver disease |

None |

5,000 |

8,000-10,000 |

1,000 |

|

|

|

Figure 2

Figure 2

Hepatitis A virus

CDC |

INFECTIOUS HEPATITIS - HEPATITIS A VIRUS

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) (figure 2) causes infectious hepatitis which is transmitted via

the oral-fecal route as a result of close contact such as in day-care

centers. The virus is also spread by sexual contact and in contaminated

food. Rarely (in fewer than 1% of cases) is HAV spread by blood

products, blood transfusions or intravenous drug use.

This form of hepatitis accounts for about 40-50% of all hepatitis cases

(figure 1). The

orally ingested virus first enters the bloodstream via the lining of the

intestinal tract and then migrates to the liver parenchymal cells. These

cells become infected because they have the immunoglobulin-like HAV cellular

receptor on their surfaces. The virus replicates rather slowly and is shed into the bile and passed in the stool. The symptoms of HAV

and HBV are very similar. There is only one HAV serotype worldwide and

humans are the only reservoir.

|

| |

Symptoms

The most obvious symptom is jaundice. HAV also causes abdominal pain, nausea

and diarrhea. In addition, the patient may suffer fatigue and fever. Chronic

infections with HAV do not occur but some patients may experience symptoms

for up to 9 months.

|

| |

Carcinogenesis

There is no evidence for HAV being the cause of liver cancer (hepatocellular

carcinoma).

|

Figure 3

Figure 3

Events in hepatitis A infection CDC |

Immune response

Virus particles are found in the bloodstream from three days to five weeks

after infection and in the stool from one to five weeks after infection. In

the latter part of this period, raised liver enzymes in the bloodstream

(e.g. alanine amino transferase) are observed. IgM (which is used in

diagnosis) rises soon after the initial infection and peaks at about 5

weeks. Anti-HAV IgG rises later (two to three weeks) (figure 3). There is a cytotoxic T

cell and natural killer cell response that kills infected cells. The humoral

response is also important in counteracting the virus but most pathological

effects of the virus are the result of the immune response rather than the

virus itself. Once the patient has cleared the virus, the anti-HAV IgG antibody response

gives life-long protection.

|

Figure 4

Figure 4

Concentration of HAV in various body fluids CDC |

Pathology

There is a prodromal (incubation) phase of between two and eight weeks after

infection, following which there is an abrupt onset of symptoms. After about two weeks of infection, virus is detectable in the

liver, blood and stool (Feces can contain up to 108 infectious

virions per milliliter and are the primary source of HAV) (figure 4). The virus replicates in hepatocytes but little

cellular damage ensues. Thus, the symptoms of infectious hepatitis are not

caused by the presence of HAV in the liver but by the immunological response

of the host to its presence. Initially, patients experience fatigue, pain in

the abdomen and nausea and there are elevated levels of liver enzymes in the

serum

A few days after the first symptoms, jaundice (icteric symptoms) often

occurs; this is particularly noticeable in the sclera. Jaundice is seen in

about 60% of adults but far fewer children (up to 20%). There is also dark

urine and light stool. Children show lesser symptoms than adults; for

example, jaundice is seen among fewer than 10% of children younger than 6

years of age, 40%-50% of older children and 70%-80% of adults.Almost all

(99%) patients make a complete recovery within two to four weeks with no

chronic sequelae. In about 0.1% of patients, fulminant hepatitis occurs

leading to death in the majority of these patients (about 50-80%). This results

from liver failure and encephalopathy. Other rare complications are

relapsing hepatitis and

cholestatic hepatitis (in which there are very high

bilirubin levels). The former, which has

symptoms similar to the original infection, usually occurs within three

months of the initial HAV infection. In cholestatic hepatitis, liver damage

by the virus occurs leading to obstruction of bile secretion. This is most

often seen in immuno-compromised patients.

|

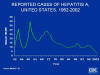

Figure 5

Figure 5

Risk factors for hepatitis A in United States CDC

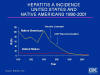

Figure 6A

Figure 6A

Reported Hepatitis A Cases, By Year Northern Plains Indian Reservation,

South Dakota, 1968-2002 CDC

Figure 6B

Figure 6B

Incidence of hepatitis A in American Indians 1990-2001 CDC

|

Epidemiology

The incidence of HAV infection in the United States has fallen from about 12

cases per 100,000 population in the 1980ís to 2.9 in 2002 (figure 7B). This is largely

due to the availability of the vaccine. In 2001, there were 93,000 new HAV

infections in the United States. There were an estimated 45,000 acute

clinical cases (but many fewer were actually reported). in the United

States, hepatitis A outbreaks used to occur in 10 to 15 years cycles.

Since transmission is via the oral-fecal route, members of the family of an

infected person are most at risk. Community outbreaks are common but in half

of all cases no risk factor is identified (figure 5). The infected person is contagious

before overt symptoms appear. Many infected persons are asymptomatic (most

children and up to a half of infected adults) but still shed infectious

virus. In addition, conditions of poor housing and cramped conditions lead

to spread of the virus. There are frequent outbreaks in daycare centers that

are then transmitted to other family members. The virus is also transmitted

as a result of sexual contact, especially homosexual sex and, since it is

blood-borne, can be spread by sharing needles during use of intravenous

drugs. The virus is very resistant to a variety of agents including low pH,

organic solvents and detergents. It is also resistant is temperatures as

high as 61 degrees for 20 minutes. Besides direct fecal-oral transmission

(such as by contaminated hands), the virus may be spread in contaminated

drinking water and where raw sewage is present since the virus can survive

for months in fresh or salt water. Particularly problematic is sewage

contamination of oysters and other shellfish that are filter-feeders. In

developing countries, most people get mild HAV infections as children and

then retain life-long immunity. Approximately 30% of the population of the

United States is seropositive with a much higher incidence in third world

countries.The highest rates of hepatitis A in the United States are found

in Hispanic and Native American populations (figures 6, 7D). The lowest are among Asian

Americans. This undoubtedly reflects socio-economic conditions such as

crowding and also contact with persons from countries such as Mexico with

high HAV infection rates. These factors result in higher hepatitis A

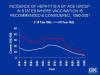

incidence in western states (figure 7A, G, H). In 1990, hepatitis A incidence was highest in

children (figure 7C) with about an equal male to female ratio; however, by 2001, the

gender/age incidence had changed markedly with the highest incidence in

young to middle aged men (figure 7 I, J). This is because the incidence of hepatitis A has

fallen as a result of vaccine use and HAV is now mainly spreading among

intravenous drug users and homosexual men.

The virus is found worldwide with the highest levels in under-developed

countries (figure 7E). In underdeveloped countries, nearly all children have anti-HAV

antibodies indicative of a prior infection and epidemics are rare. In

countries with higher levels of sanitation, infection occurs in older

individuals and clinical disease is more often seen; very often there are

localized outbreaks. In some countries with high hygiene standards (e.g.

Scandinavia), clinical disease outbreaks are again rare and hepatitis A is

seen primarily in intravenous drug users.

|

Figure 7

A.

Distribution of hepatitis A in the United States by county CDC |

B.

Reported cases of hepatitis A in the United States 1952-2002 CDC

B.

Reported cases of hepatitis A in the United States 1952-2002 CDC

C.

Incidence of hepatitis A by age group 1990-2001 CDC

C.

Incidence of hepatitis A by age group 1990-2001 CDC

D.

Incidence of hepatitis A by race in United States CDC

D.

Incidence of hepatitis A by race in United States CDC

E.

Global distribution of hepatitis A CDC

E.

Global distribution of hepatitis A CDC

G.

Hepatitis A incidence in United States. Comparison of 1987 - 97

average with 2002 CDC

G.

Hepatitis A incidence in United States. Comparison of 1987 - 97

average with 2002 CDC

H.

States with highest hepatitis A rates CDC

H.

States with highest hepatitis A rates CDC

I.

Hepatitis A in the United States by age and gender 1990 CDC

I.

Hepatitis A in the United States by age and gender 1990 CDC

J. Hepatitis A in the United States by age and gender

2001 CDC

J. Hepatitis A in the United States by age and gender

2001 CDC

|

F.

Hepatitis A Incidence, United States,

F.

Hepatitis A Incidence, United States,

1980-2002 |

| |

Diagnosis

An ELIZA test for anti-HAV IgM is available. Diagnosis is also made from the

symptoms and the clusters of cases that occur. The presence of IgG within

the first few weeks of infection suggests a prior infection or vaccination.

|

| |

Treatment

There is no treatment. Supportive care should be given. Hepatitis A immune

globulin can be administered early after infection (two weeks) and gives

some temporary immunity (up to five months).

|

| |

Control

Improved hygiene is the most important factor in stemming the spread of HAV.

Chlorination of water is very effective. Before the present vaccine, passive

immunity was obtained using immune gamma globulin which was effective

against the disease in most cases if given before infection as prophylaxis

or during the early incubation period. The present very effective vaccines (HAVRIX

and VAQTA) used in the United States are killed (formalin) virus preparations. The

vaccine is given in the first year of life and immunity, probably life-long,

results within a month. In adults, the vaccines give protective immunity

within one month of vaccination in most recipients. A second dose leads to

100% protection.

|

| |

There is a combined anti-HAV/HBV vaccine approved in the United States for

recipients of 18 years and older. It contains Hepatitis A antigen and HBsAg.

In other countries, this vaccine is available for children.

|

| |

ENTERIC NON-A, NON-B HEPATITIS

- HEPATITIS E |

Figure 8

Figure 8

Geographic distribution of hepatitis E CDC |

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) causes enteric non-A,

non-B hepatitis and is transmitted via the oral-fecal route through

contaminated drinking water. It is not usually transmitted directly from one

patient to another (in contrast to HAV). HEV outbreaks can be extensive and

is likely the cause of much of the acute sporadic hepatitis seen in areas

where the virus is found (figure 8). In countries of low incidence, HEV infections are

usually seen in travelers.

After an incubation 16 to 60 days (with an average of 40 days), typical

hepatitis symptoms arise (jaundice, malaise, abdominal pain, nausea etc).

Virus may be excreted in the stool for several weeks after the onset of

symptoms. There is no evidence for chronic HEV infections but persistence in

the population may be the result of a low level of infections between

epidemics. In pregnant women the mortality rate is high.

|

Figure 9

Figure 9

Hepatitis E infection - Typical serologic course CDC |

Immunology

After a prodromal phase of about a month, symptoms occur. Virus is found

earlier in the stool . Alanine aminotransferase rises at the same time anti-HEV

IgM and IgG. By about two months, elevated alanine aminotransferase

diminishes, as does IgM. IgG remains and results in short term immunity

(figure 9).

Diagnosis

There are no commercially available tests for routine diagnosis

|

| |

Epidemiology

HEV is endemic to many tropical countries where good sanitation is lacking.

In the United States less than 2% of the population has anti-HEV antibodies.

The source of these infections is not known.

Prevention

Possibly contaminated drinking water should be avoided as should uncooked

food in endemic areas. Immune globulin is not effective if it comes from

donors in western countries. There is no vaccine.

|

|

Return to the Virology section of Microbiology and Immunology On-line

Return to the Virology section of Microbiology and Immunology On-line

This page last changed on

Friday, February 05, 2016

Page maintained by

Richard Hunt

|

Figure 1

Figure 1 Figure 2

Figure 2 Figure 3

Figure 3 Figure 4

Figure 4 Figure 5

Figure 5

D.

Incidence of hepatitis A by race in United States CDC

D.

Incidence of hepatitis A by race in United States CDC G.

Hepatitis A incidence in United States. Comparison of 1987 - 97

average with 2002 CDC

G.

Hepatitis A incidence in United States. Comparison of 1987 - 97

average with 2002 CDC I.

Hepatitis A in the United States by age and gender 1990 CDC

I.

Hepatitis A in the United States by age and gender 1990 CDC F.

Hepatitis A Incidence, United States,

F.

Hepatitis A Incidence, United States, Figure 8

Figure 8 Figure 9

Figure 9